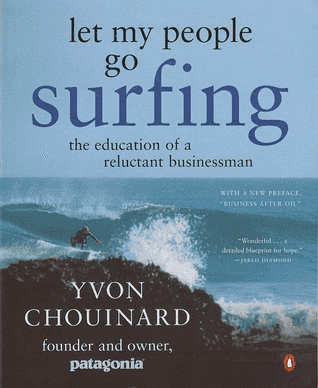

Notes from Let My People Go Surfing by Yvon Chouinard

This books is part memoir, part philosophical manifesto derived from Patagonia’s founder’s experience in applying them to business, environment, and life.

I skimmed some parts of this book like the parts laying out the design and product philosophies, written in a handbook-style, knowing that I wouldn’t be able to fully appreciate their depth at this point in my life. I’d return to it when I’m running my own business, if that day returns!

I strongly recommend this book to anyone who wants to learn:

- How to actualise environmental ethics as business practices

- The right kind of growth for one’s business

- The philosophies that made Patagonia one of the world’s most respected companies

On mastery and perfection

Early in the book, Yvon quoted French writer Antoine de Saint-Exupery about how perfection in design is achieved when there is no longer anything to take away and how it relates to mastery of a skill:

It is as if there were a natural law which ordained that to achieve this end, to refine the curve of a piece of furniture, or a ship’s keel, or the fuselage of an airplane, until gradually it partakes of the elementary purity of the curve of the human breast or shoulder, there must be experimentation of several generations of craftsmen. In anything at all, perfection is finally attained not when there is no longer anything to add, but when there is no longer anything to take away, when a body has been stripped down to its nakedness.

Then, in the last few pages of the book, Yvon reiterates a similar point:

The ship’s carpenter on Shackleton’s lifeboat the James Caird took only three simple hand tools with him on the passage from Antarctica to South Georgia Island, knowing that, if he needed to, he could build another boat with only those tools.

I believe the way toward mastery of any endeavor is to work toward simplicity; replace complex technology with knowledge. The more you know, the less you need.

The more you know, the less you need. The less you incorporate, the closer the thing you are working on reaches perfection. As someone who codes software applications at work, I have seen this logic play out many times. I’d regularly be surprised at how, upon pause and code re-write, the same outcome can be achieved with fewer computational steps, fewer lines of code, and more easily understood code.

From what I can tell, Yvon does not call on everyone to strive for perfection nor mastery. He did, after all, describe himself as an “80 percenter”:

I’ve always thought of myself as an 80 percenter. I like to throw myself passionately into a sport or activity until I reach about an 80 percent proficiency level. To go beyond that requires an obsession and degree of specialization that doesn’t appeal to me. Once I reach that 80 percent level I like to go off and do something totally different; that probably explains the diversity of the Patagonia product line—and why our versatile, multifaceted clothes are the most successful.

I think he talks about mastery and perfection as ideals that are worthy of our pursuit, so that we may end up creating products that are excellent. The 80 percenter side of him (which I relate to strongly because I also identify in myself) is what he attributed to the diversity of the product line at Patagonia, from safety equipment to apparel, that gives the company the uncommon ability to do what few other companies would do.

Environmental ethics as business practices

One of the things that Patagonia is known for is its heroic commitments to environmental causes.

The first time Yvon did this was by removing pitons from its product line when he noticed that their use led to disfigured mountain faces:

By 1970 Chouinard Equipment had become the largest supplier of climbing hardware in the United States. It had also started down the path to becoming an environmental villain. The popularity of climbing, though growing steadily, remained concentrated on the same well-tried routes in leading areas such as El Dorado Canyon near Boulder, the Shawangunks in New York, and Yosemite Valley. The repeated hammering of hard steel pitons, during both placement and removal in the same fragile cracks, was severely disfiguring the rock. After an ascent of the Nose route on El Capitan, which had been pristine a few summers earlier, I came home disgusted with the degradation I had seen. Frost and I decided we would phase out of the piton business. This was to be the first big environmental step we were to take over the years. Pitons were the mainstay of our business, but we were destroying the very rocks we loved. Fortunately, there was an alternative to pitons: aluminum chocks that could be wedged by hand rather than hammered in and out of cracks.

I was a little sceptical as this read like marketing copy that tries to construct a story that fits the events. But later in the book, Yvon explains that in 1986 and for every year since then, Patagonia has donated 10 percent of profits each year to small environ=mental groups working to save or restore natural habitat:

The development plan was defeated. We gave Mark office space, a mailbox, and small contributions to help him fight the battle for the river. As more development plans cropped up, the Friends of the Ventura River worked to defeat them and to clean up the water and to increase its flow. We lobbied for a second stage on the sewer plant and then a third. Wildlife increased, and a few more steelhead began to spawn. Mark taught us two important lessons: A grassroots effort could make a difference, and degraded habitat could, with effort, be restored.

Inspired by his work, we began to make regular donations to small groups working to save or restore natural habitat, rather than give the money to large NGOs (nongovernmental organizations) with big staffs, overheads, and corporate connections. In 1986, we committed ourselves to donate 10 percent of profits each year to these groups. We later upped the ante to 1 percent of sales, or 10 percent of pretax profits, whichever was greater. We have kept that commitment every year, boom or bust.

Another way that Patagonia actualises environmental ethics as a business practice is by maintaining an unwavering commitment towards durable goods:

We let our customers tell us how much we should grow each year. Some years it could be 5 percent growth or 25 percent, which happened during the middle of the Great Recession. Consumers become very conservative during recessions. They stop buying fashionable silly things. They will pay more for a product that is practical, multifunctional, and will last a long time. We thrive during recessions.

It helps that they were a company that comprised people who used their products, effectively “dogfooding” before the term became a hot phrase in Silicon Valley:

Quality control was always foremost in our minds, because if a tool failed, it could kill someone, and since we were our own best customers, there was a good chance it would be us!