Not interested in mastery

I can code and I think I can code well. But for some reason, I’m just not inclined to try and become an amazing programmer. For me, with programming as with many other skills, I ascribe to the mantra that good enough is good enough. Why pace the long end of the curve of diminishing returns? I just see no point in it.

The founder of the visionary outdoor apparel company Patagonia, Yvon Chouinard, says the same about himself in his memoir Let My People Go Surfing (my notes):

Once I reach that 80 percent level I like to go off and do something totally different; that probably explains the diversity of the Patagonia product line—and why our versatile, multifaceted clothes are the most successful.

The point is, once he realised that he has become good at something, he looks for a new challenge.

About four years ago I graduated from a programming bootcamp, going from knowing nothing about software programming to getting hired as a junior software developer at a startup.

In one year of coding daily, maintaining a code base and building upon it to deliver features to our users then, I felt like I had learned 80 percent of what needed to be learned for me to be an effective programmer. Now I’m confident that I’d be able to build at least the first version of almost any software product should an idea come along. Good-enough skill level acquired, so I moved on.

I then started to teach others how to code at programming boot camps. It was fulfilling but after each cohort, I would feel drained, in need of something else to work on. (I still haven’t been able to shake off that post-teaching fatigue even now. Not sure what it is.)

Anyway, a few teaching stints later, I landed my current job as a “service operations engineer” at a Finnish advertising tech company, Smartly.io. I’ve been here for almost two and a half years. Coding is only part of my weekly work in this role so I haven’t grown a lot in terms of technical skills since my full-time software engineering days, and the point is, on most days, neither do I feel like that’s a problem. I just am not that interested in getting too good at something.

Rather, I consider myself lucky to have been given the freedom to improve at other skills, like team project management, customer service, interviewing, internal communications, technical writing, and leadership. Now I’m on my way, hopefully far along, to being good enough at those skills too.

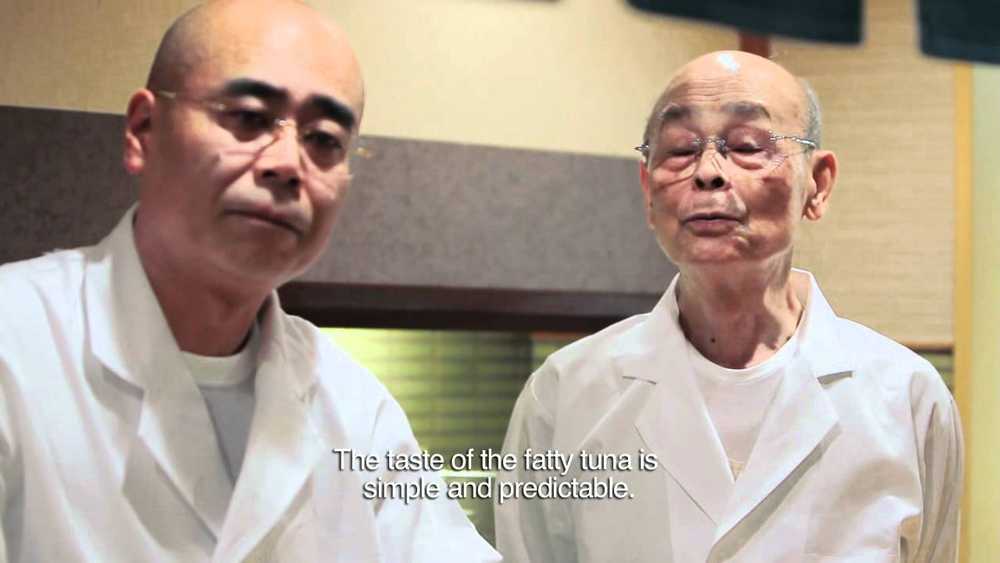

A scene from Jiro: Dreams of Sushi (2011)

A scene from Jiro: Dreams of Sushi (2011)

When I sit down and rationalise things this way, everything seems okay. But the truth is, I regularly second-guess myself about whether I ought to specialise more. Go deep, like that sushi chef from Jiro: Dreams of Sushi who has been making sushi his entire life and is darned good at it. Or like a more recent and much closer to home example, my classmate Kenneth Foong, who, after a decade of pursuing his craft as a culinary chef, recently got appointed as head chef at Noma, the world’s top restaurant. I mean, going deep on a single skill — cooking — turned out great for these guys.

Each time I question my decisions, I make myself feel like crap. But at some point, we have to come to terms with who we are. I am simply not interested in becoming excellent at something by mastering one or two skills. I would much rather become excellent at something because I am good-enough at ten different skills.

I’m currently working on getting good at writing.

Update in 2022

As I’ve started in an individual contributor role as a senior software engineer at Shopify, I’m beginning to re-evaluate this once again. I feel like I’m definitely going to need to go further on the mastery curve for software engineering to be able to build the product for millions of users; I think I’d be irresponsible if I believed otherwise.

That said, I still feel that deep down I prefer being valuable by knowing a range of things relatively well (and letting them blend) rather than knowing a craft extremely well. I don’t think it’s necessarily one or the other since how well one knows something lies on a spectrum.