The Untouchable Space Between Stimulus and Response

One of my favourite quotes is by the Austrian psychologist and Holocaust survivor, Dr Viktor Frankl:

Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.

When I am angry, upset, happy, or disturbed by something, I always try to return to this quote. It reminds me of this special space in my mind and its wondrous ability to help me see things for what they are.

This space exists solely in each of our minds. Nobody can be in this space of yours but you.

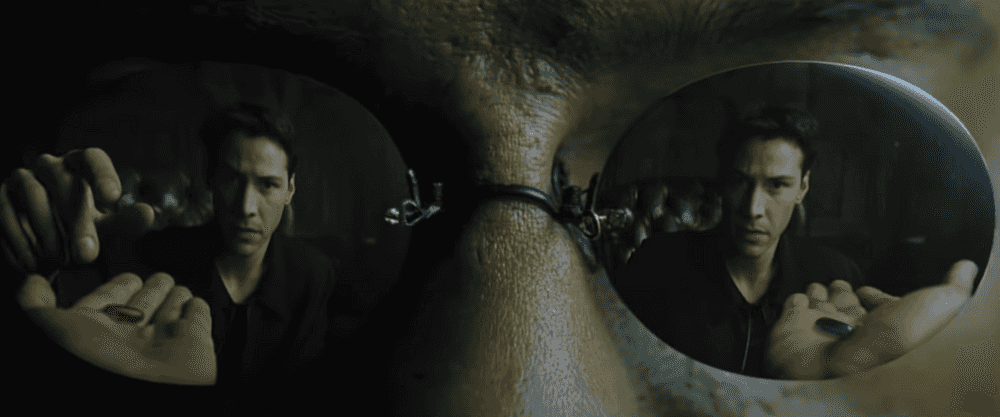

Scene from The Matrix where Neo takes the red pill from Morpheus.

Scene from The Matrix where Neo takes the red pill from Morpheus.

Recognising that this space exists and that one can make use of it anytime to construct a response is probably one of the most impactful revelations one can have. Its profundity is akin to having taken the red pill and being awoken from The Matrix, and all it took to get started was to be aware.

Once I knew about this and managed to use it in practice a few times, my quality of life has improved in irrefutable ways.

To understand why and how life can improve by knowing and using this space, we must begin by talking about what is meant by stimulus and response.

Life is a series of stimulus-response cycles

A stimulus is something, usually external, that excites or arouses the mind or spirit.

A response is an answer to something.

When someone laughs at you, that is an external stimulus. What you do next might include being embarrassed and barking back, and that is your response.

When you subconsciously worry, that is an internal stimulus. What you do next might include negative self-talk, and that is your response.

How you act is a response.

It is easy to acknowledge this because intuition tells you that nobody can make you do what you don’t wish to do. Your school teacher could not make you do your homework if you did not willingly want to do it. If punishments can definitively control us, we would live in a world without delinquency.

What we don’t often think about is how this also applies to the level of perception.

How you perceive is also a response.

If you said something on Facebook and someone rebukes it publicly, you might see that person as challenging you to a debate. Alternatively, you could also see that person as trying to help you learn.

And if you go one level lower, at perhaps the most fundamental level of human being, we arrive at our feelings.

How you feel is a response

Here, most people would instinctively disagree. I did too, at first. But how you feel is also a response.

People don’t make you angry so much as you let them make you angry.

People don’t make you feel inferior so much as you let them make you feel inferior.

And here is the uncomfortable truth: people cannot make you feel discriminated against. You can choose to not let them make you feel that way and instead, choose a different response like striving for the life you want in spite of them.

The key is to recognise that every response you have is a response you let yourself have.

Of course, it’s not so simple. We also have a subconscious mind that takes the space over when we’re not paying attention.

If how you feel is a response, then it means that by the time you feel a certain way after encountering a stimulus, you have already passed that space between stimulus and response.

In the earlier scenario of discrimination, your subconscious mind is likely to choose to perceive that you are being profiled and discriminated against and go into “I am not your lunch” mode, making you puff up your chest, ready for a fight.

The good news is, if you want to feel a different way, you can simply go back to that space and alter your response.

Here are 4 ways in which taking control of our responses can improve our lives.

1. You become kinder to yourself

The biggest improvement comes from disliking yourself less.

Let’s say that you wrote an article and you shared it on Facebook. The next day, you wake up to find multiple people openly disagreeing with you.

Now you feel stupid because someone saw your point and rebuked it. Why didn’t I think of that myself? I could have saved myself some embarrassment.

You feel hurt because now your social standing among your friends has deteriorated and you start to feel inferior. Everyone seeing this post must think that I’m lame.

These are feelings I had recently when I shared my opinion that it is okay to disengage from politics. When I read people’s replies on Facebook, I felt like I was being attacked. I felt a little stupid. And I certainly felt like I’ve lost the respect of some people.

But over the next few days, I remembered about the space that exists between stimulus and response.

I saw that someone’s disagreement was the stimulus and that I chose to respond by letting their comment make me feel like I was being attacked, that I was stupid and that I have lost the respect of other people.

Once I noticed that I was able to choose to see those disagreeing comments for what they were: disagreeing comments.

I was not being attacked! Discourse requires people to go back and forth disagreeing until an agreement is reached.

I am not stupid! If I knew everything and was right about everything, I would have found no reason to write and share my writing with people in the first place.

Now, I might have lost someone else’s respect, but what someone else thinks about me is a response from that person’s mind and therefore beyond my control. It is pointless to mull over what only exists in someone else’s headspace.

Much of the day-to-day suffering that we experience comes from us letting that space be controlled by the terrible autopilot that is our subconscious mind.

The moment we remember this, we regain control of that space and it becomes easy for us to be kinder to ourselves.

2. You become kinder to others

Here’s another example, this time to illustrate the difference in how we treat other people when we remember to take control of this space.

On a recent morning walk with my partner and dog, I decided to stop by the local cafe to grab a cup of coffee.

It was Sunday so the cafe was empty. I walked in and placed my order with one of the two men behind the counter. I paid and stood aside to wait for my coffee.

I like to watch the barista making my coffee. It’s a craft. However, I soon noticed that something was amiss.

One of the men was clearly more experienced than the other in making coffee as I could see him appraising the other’s every move. The first shot of espresso was apparently not done well, so the experienced barista poured it away and instructed the trainee barista to try again and pull a second shot. He did the same with the milk.

As I continued to observe what was happening, I started feeling uncomfortable. I was anticipating the coffee to be bad. Having been a barista before, I knew how hard it was to pull a good shot of espresso and froth a jug of smooth milk.

The trainee barista pulled a new shot, frothed a new jug of milk, made a cappuccino, and served it to me in a paper cup.

It was a poorly made cup of coffee. The milk foam was not so much froth as it was a bubbly mess.

At this point, my subconscious mind went on autopilot and put together a narrative of what was happening:

There was nobody in this cafe today and yet, they took twice the time to make my cup of coffee because of the retry. The retry that, by the way, caused some coffee and milk to be wasted. My partner and dog have been waiting outside and I feel bad. And in the end, they served me a cappuccino that looked like a baby had drooled all over it.

This got me worked up. Or I should say, I let this get me worked up. I felt like I needed to teach them a lesson. I felt like I had to tell them that this was unacceptable. That I was paying them 3 € for a cup of coffee and that they should not use my coffee for training.

But, perhaps due to the meditation that I did in the morning, despite that narrative dominating my mind, I managed to pause and remember that between the stimulus and response is a space that I controlled.

Now that I was in that space, one thing became immediately clear: this was a trivial matter. It is a cup of coffee, Nick.

I instinctively tapped the cup of coffee against the countertop to break the larger bubbles on the surface of my coffee, a habit I still have from my barista days.

In the space in my mind, I had what was a conversation with myself.

Yes, they made me wait a while for poorly-made coffee. But they did not do it deliberately to upset me. In fact, as with most things done by most people, they probably did none of it with me in mind at all. Here is just a guy who is trying to learn to make good coffee. He is clearly not there yet and needs more time. We all need time to learn, don’t we? Heck, even Einstein used to not know physics. Also, don’t forget how you had to learn slowly to become a decent barista by serving sub-standard coffee, too.

Once I had that internal dialogue, which happened purely in that space in my mind between the stimulus and my response, I no longer let myself get worked up.

I chose a different response. I picked up the coffee, said thank you, and rejoined my partner and dog.

The coffee turned out to be not as bad as it looked.

Post-incident, I reflected and realised how glad I was to not have lashed out on the trainee barista. Not only did I manage to not ruin his confidence of being a barista, but I had also indirectly aided him in his journey to becoming a trained barista by paying for his practice coffee.

The blue in the sky looked a little more vibrant later that morning.

3. You help yourself learn faster

When you pause in the space before responding, you improve your chances of having a constructive conversation with someone. In this way, you help yourself learn and grow faster.

Let’s revisit the Facebook post example.

When I read the first few disagreements, I was initially able to respond from the space, calmly and rationally.

But soon, someone wrote his disagreement with stronger words like “ignorant,” which felt like a blade on flesh. I could feel the blood that oozed boil off.

Instead of considering his argument, I latched on to his accusation and, unthinkingly, I responded with a snarky comment. In hindsight, it is clear to me now that that was the moment my subconscious mind took control of the space.

That person never replied. Later, someone who saw the way I responded called me out for it and that shook me into regaining control of my mind.

Things once again became clear to me.

What I had effectively done was let myself be angered by that comment. That was my first response. And my second response was to send the snarky comment.

And what was the outcome? I shut the door to dialogue with this person and probably blew the chance for us to learn from each other again. This person isn’t worth my time arguing with, would be a reasonable conclusion on his part.

If you remember to use the space before responding, you will learn faster by making it safe for others to teach you what they know.

And if you find what someone says disagreeable, and you are in that space, you might manage to empathise with that person better. Perhaps he was not using his space between stimulus and response. Then, all that you can do is to let silence do its thing.

4. You deal better with hardships

And finally, when you sometimes face inevitable and undeniable hardship, you can use this space as a refuge.

“Between stimulus and response there is a space. In that space is our power to choose our response. In our response lies our growth and our freedom.” (emphasis mine.)

These are words from someone who had endured life in several Nazi concentration camps, survived, and continued to live after the war. Dr Viktor Frankl unsurprisingly struggled to find meaning in life when he, along with his fellow prisoners, was treated worse than animals in the camps.

“[m]an is that being who invented the gas chambers of Auschwitz,” he said in Man’s Search For Meaning. “However, he is also that being who entered those gas chambers upright…”

What he means by this is that even down to the forceful and tragic end of one’s life in a gas chamber, one still owned the freedom to choose how to respond.

That is the nature of the space between stimulus and response. It is untouchable by anything and anyone but you. It is the only true freedom that we have been afforded as humans!

Few of us will have to endure this level of hardship now, but there remains awful plenty of hardships in life.

For our tribulations, we can safely say that we, too, get to choose our response.

Start responding better

Awareness alone is enough for us to benefit from this space.

Life consists of unceasing cycles of stimuli and responses and therefore, to live well in the face of real or false adversity, we have to learn to respond to each stimulus with intent.

The best way we can do this is by remembering about the special, untouchable space that exists between detecting a stimulus and choosing a response.