Types of Notes in a PKM explained with a Gardening Analogy (Part II)

This is part II of Types of Notes in a PKM explained with a Gardening Analogy (Part I of II).

In part I, we talked about how everything in a personal knowledge management (PKM) system is focused on building atomic notes through various stages of maturity. We also talked about how other types of notes can help us in that life-long endeavour, discussing in detail the Top of Mind note — the first type of “other” notes.

In this second part, we will talk about the remaining types of notes that could be useful as tools in your PKM garden, including:

- Daily note

- Index note

- Outline of external resources

- Map of content (MOC)

2. Daily note

Seasons change, weeks are completely human-made, but the day has a rhythm. The sun goes up; the sun goes down. I can handle that. Austin Kleon

i. Tracing the origin of ideas

I have written in detail about the purpose and function of a daily note in my PKM before. Here is the one-sentence summary: daily notes let me navigate back in time and regain context of the origin of ideas.

You might perhaps be a little puzzled: didn’t you say earlier that you put your ideas in the top of mind note? Why would ideas appear in your daily note? Yes, I said that but as it turns out, ideas are not equal, and I needed a way of dealing with the less interesting ones.

Also, it’s important to me to not only have a process for capturing important or urgent things but also the purportedly “unimportant” and not urgent things, because those things often end up being interesting:

Everything interesting begins in the “unimportant and not urgent” quadrant. Eliminating it is the dumbest thing you can do and the worst advice Covey gave.

— Venkatesh Rao (@vgr) August 10, 2021

To illustrate the range of ideas that can come up in a normal day for me, here are a few scenarios:

- John tells me something about parenting at the office pantry. Something about “the Maya method.” I am about to become a parent and have been looking for things to read.

- I was in the toilet scrolling LinkedIn and noticed a post that my old uni friend Junqi shared about a book that has helped him lead his team with more authenticity. I am also a manager at work and I’d like to improve my leadership. This isn’t a priority for me right now, though, since I’m about to go on parental leave.

- I purchased new screenshot-making software and shared it on Twitter. Some people responded saying that they’d love to read my review of it. I hadn’t thought of writing a review, but I’m seeing that it could be useful to some people.

In some of the scenarios above, I can sense that there is a kernel of an idea that I can’t wait to crack open. In other scenarios, the idea feels only mildly appealing, although still worth capturing. Future me might love it.

So, what do I do with these in my PKM? I know I’d like to capture them somehow for rediscovery. But how?

Here’s what I would do:

- Write “Read about Maya method that John talked about” in the Top of Mind note’s inbox and follow up within the next few days.

- Write “Junqi shared on Linkedin (link) about reading the book

[[b-7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey]]and that it helped him with leadership. Maybe worth reading.” in my Daily Note, and potentially follow-up the next time I’m looking for a book to read. - Write “A few people are interested in a review of CleanShot screenshot software.” in my Daily Note along with relevant links (e.g. a Twitter thread), and then add the tag

#🌐in the same sentence, and potentially follow-up the next time I’m looking for blog article ideas.

(Primer on linking to yet-to-exist notes: In point 2, I created a link to the yet-to-exist note entitled 7 Habits of Highly Effective People by Stephen Covey. Most PKM software will soft-create a note for you in the background when you try to link to a note that does not exist in your PKM yet. In Obsidian, you can toggle off a setting under the Quick switcher > Show existing only. In the future, when you type double brackets or search for a file, Obsidian will then search among soft-created notes as well.)

Okay, so imagine that you’ve done exactly what I said above in your PKM. Let’s focus on points 2 & 3 as they involve the daily note. How can you trace the origin of ideas? Why is that useful in the first place?

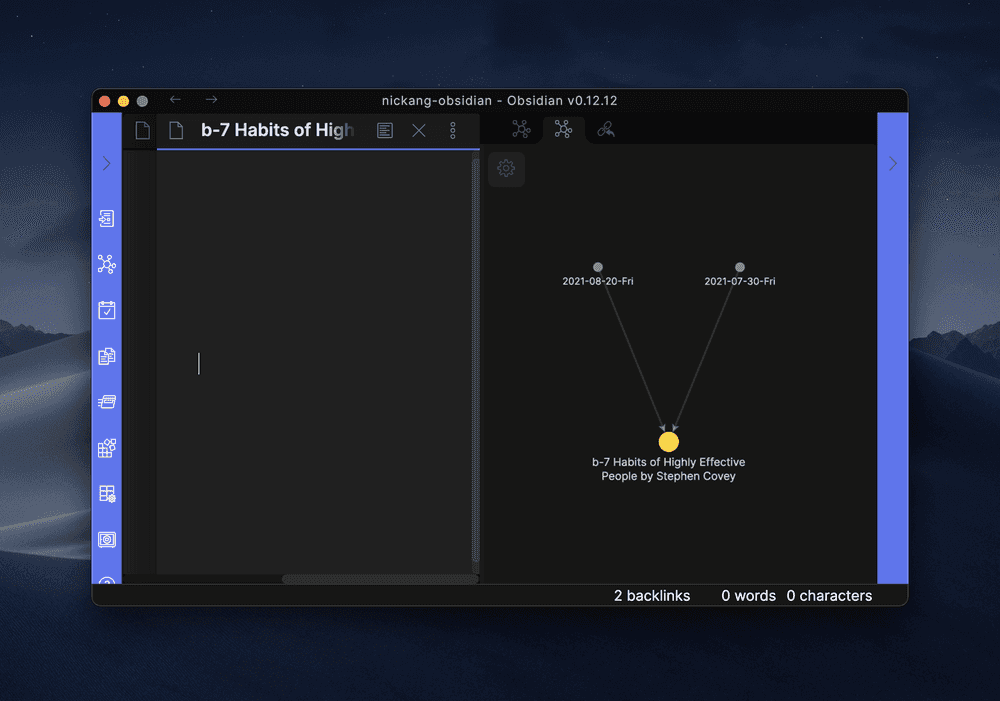

Say, 3 months later, someone else mentions the 7 Habits book to you. This time, you follow the same process and as you type two square brackets in that day’s daily note, to your surprise, you notice the full name of the book showing up in auto-complete.

Huh, I’ve jotted down this book once!, you think to yourself. This piqued your curiosity and so you link to that still-yet-to-exist note and finally create an empty note with that title (a simple Cmd + Click in Obsidian) since you have a feeling you’ll want to read it soon now that two people you know have talked about the book.

Now, because of your PKM software, you have in your hands an empty note that has two incoming links. In Obsidian, one way to view incoming links is using the Graph View, and it would look like this when viewing the newly created book note:

You can literally see the context unfurling in front of you.

You can literally see the context unfurling in front of you.

Being able to look at the note from the specific day you first thought about a book allows you to almost travel back in time to see who recommended it, why, and what you thought when you wrote it in that day’s daily note in the first place.

You can then compare your past self to your present self and make a judgement about what to do next. Perhaps, you think, you should add “read this book” to your top of mind inbox!

For this time-walk to work, we need the daily note to be as vivid and context-rich as possible. The more details from that day, the more context to come back to. Thankfully, this can come quite naturally by thinking of your daily note as a scratchpad.

ii. A scratchpad

My mental model of the daily note is a scratchpad. It just so happens to have software-enabled superpowers.

In the earlier section, I shared how you can trace ideas to their origin in your PKM and why that can be useful in the long run. Now let’s talk about how to make that origin as context-rich as possible without additional effort.

This description is going to be surprisingly short. You can set yourself up for success by making these your “sensible defaults”:

- Set your PKM’s default launch page as today’s daily note

- Set up a daily note template with two sections to begin with: work, personal

- If you use templates, add a created timestamp that auto-fills the day’s date according to the filename of your daily note

Whenever I have a quick idea to jot down, I’ll launch the Obsidian app and it loads automatically to that day’s daily note. I then do a couple of line breaks and write down the thought.

This is especially helpful for rough thoughts that I’m unsure if I want to develop, but for which I should know by the end of the day. Since I keep defaulting to the daily note throughout the day when I launch the Obsidian app (same behaviour on both mobile and desktop), I know there is a high chance that I will stumble on this again before the day ends.

In short, use the daily scratchpad for everything transient and for follow-ups that feel less important or unsure-how-important. In contrast, the top of mind note is reserved for important or urgent follow-ups that you know you don’t want to miss.

The third point about adding a timestamp to templates is to automatically create an explicit connection (in the form of a double-bracketed backlink) from any newly created note that uses a template to that day’s daily note. This has helped me on several occasions to retrace my steps to the day when I first considered an idea.

Using a template that has a macro adds the day’s timestamp in the same format as my daily note’s title establishes an explicit connection with the day’s note.

3. Index note

Right, next let’s talk about the index note. I use a single index note to contain metadata relating to my PKM. The way I structure my index note is heavily inspired by Bryan Jenks’ index note. For example:

- Tag definitions

- Types of content

Tag definitions are where I explain to myself what each of the limited number of tags that I use means. Earlier in the Atomic note section of part I, I explained that I used various tags to indicate an atomic note’s maturity:

- #📤: Seedbox | items that I am / will be working actively on

- #🌱: Seedling | items grown from literature notes that still need incubation

- #🪴: Sapling | items in need of planting among other trees

- #🌲: Evergreen | fundamental unit of knowledge work, stable for dense linking to & from

- #🍓: Fruit | original work harvested from the garden

That list sits in my Index note under the “Tag definitions” section.

Next, types of content. Here’s my list:

b-: Booksv-: YouTube Videosw-: Web articles, Publications, Newspapers, Online coursesp-: Podcastsm-: Movies@-: Person

An aside about these prefixes: I prefix notes that reference external content and people with a letter followed by a hyphen, like @-John Doe or w-Nonfiction Writing Advice by Scott Alexander. This helps me search these resources more effectively because I can search by filename and type “w-” to narrow down the search to only article titles, or ”@-” to search only people’s names. Big thanks to Bryan Jenks (again) for inspiring me to do this.

In short, the index note is the living instructions manual for my PKM. Whenever I’m unsure about my workflow, I refer to this note and I’m aware again in a few seconds.

I’ve noticed that some people use their index note more like a table of content, linking to the main maps of content (or MOCs for short - more on that type of note later). You may want to experiment with that. For me, I put that at the bottom of my top of mind note instead, as it feels more like the right place for me, and I haven’t found myself needing to refer to them very often. Maybe I will when several big areas of interest emerge over time.

4. Outline of External resources

I mainly consume books, web articles, videos, and podcasts, and as a forgetful person, consuming without first annotating and later digesting information is like eating seeds; I just pass them out later without absorbing nutrients.

This is where outline notes come in.

For me, they are very similar to the map of content note (I talk about it in the next section) in that they serve as structure for making sense of a larger piece of work. Where they differ is that an outline note is for structuring external resources, and a map of content is for structuring original work.

An outline note has a more rigid structure while a map of content is more fluid (you can compare it yourself after reading about it next). If you think about it, an external resource like a book or web article is usually pre-structured with a beginning, middle, and end. Sometimes there are even page numbers (books) or timestamps (videos, podcasts). This is why I find a rigid outline format works well when trying to internalise external resources.

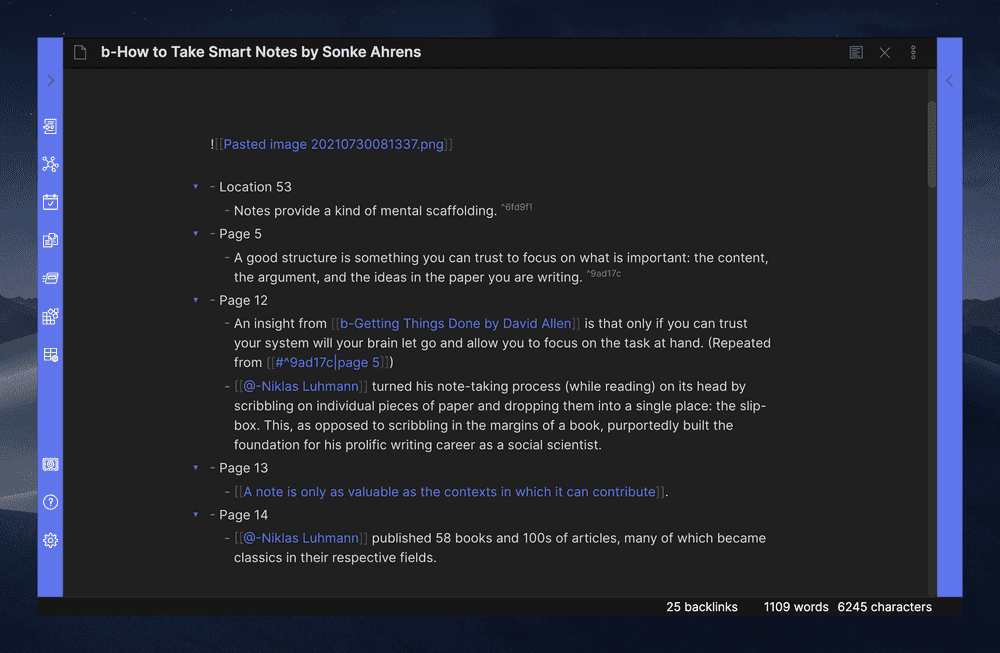

Here’s a snippet of my outline of the book [[b-How to Take Smart Notes by Sonke Ahrens]]:

Three things are noteworthy in this snippet:

- I nest each point under the page that the idea was found. This, I find, is the most lightweight technique to point to an exact part of the source. For podcasts or videos, this would be the timestamp.

- I write in my own words, rarely copy-pasting. This rule acts as a forcing function for me to understand an idea, not just be merely exposed to it and suffering the mere-exposure effect.

- Each point can be referenced anywhere in my PKM software. Notice the point in page 12 refers to the point in page 5 with the carat (

^) and randomly generated alphanumeric string.

Point 1 is probably self-explanatory. On point 2, the only time I copy-paste is if I’m trying to preserve a quote, and even then, I write my thoughts next to it.

Point 3, however, could use some explanation as it’s a new way of working with notes. It’s a feature called block references and it’s the hacker Ted Nelson’s dream come true because it fulfils the fundamental tenet of non-duplication of The Xanadu project, albeit on the smaller scale of one’s PKM rather than the worldwide web.

(Side note: block referencing is a feature that comes included in most of the popular PKM software. Obsidian, Roam Research, Logsec all have it. Conventional note apps like Bear and Evernote do not seem to support it yet.)

Why are block references useful? I have to admit, originally I didn’t get its significance either and thought of it as fancy nonsense.

Takes a deep breath. Right, but — it is extremely useful. That’s because block referencing means that once I’ve translated ideas from a book in my own words, each of those ideas become automatically atomic without explicitly making them a note of itself. As references to a particular block accrete, I take notice and eventually convert them into its own atomic note. With PKM software, you can reference any block from any note, not just from within itself.

This means that I can reference ideas within a book, web article, video, or podcast any time, from any note within my PKM, which effectively becomes an organic way for flagging up important ideas over time as references build up.

For example, if I see that there are three references to the same idea, I’d create an atomic note and write the idea in full sentences. Since I can easily find the inbound links from other notes with the alphanumeric reference numbers (handled by PKM software), I can open every inbound note and think of how they relate to and enrich the newly created atomic note.

Linked thoughts, actualised!

Over time, each outline note helps me create new, develop existing, and link atomic notes. Remember, growing the ecosystem of atomic notes is the name of the game.

5. Map of content for original work

Finally, we’ve arrived at one last type of note that I think is worth knowing about — the MOC, or map of content.

This is a term coined by Nick Milo, a person of multiple talents and interests (try boxing coach, gym owner, actor, TV editor, and YouTuber) who is a strong advocate and user of Obsidian, the PKM software that I’m using. This is the way he describes a MOC (Map of Content):

A note that mainly has links to other notes, thus “mapping” the contents of multiple notes in your digital library. MOCs help you gather, develop, and navigate your ideas. [Nick Milo](https://publish.obsidian.md/lyt-kit/Umami/MOCs+(defn)

And here, in another article, he describes his mental model of MOCs:

Using MOCs is like being in your own warehouse full of workbenches, where each workbench contains a selection of highly curated index cards for you to engage with.

I think MOCs are fascinating, and I know that I’m just scratching the surface of their utility. It’s a great concept-handle, too; its name reminds me to act like a cartographer of my knowledge.

So, when is it a good idea to try and create a MOC? For me, two main scenarios call for a MOC:

- Exploring a topic I’m very curious about (top-down)

- Experiencing a mental squeeze point (bottom-up)

Let’s talk about point 1 first.

When I’m very curious about a topic, like I was when I was trying to figure out the basic types of notes everyone should know about for their PKM, I create a MOC.

This article you’re reading started in my PKM as a top-down map of content, even though I didn’t think of it that way at first. It is top-down because I already had a topic in mind and was searching for notes relating to the topic.

Anyway, here is my process for creating a topical MOC. I create a new note, write some ideas down in bullet points, and then proceed to search through my PKM roughly like this:

- Type double square brackets and try different words, like PKM, personal knowledge management, linking, insights, thinking, etc. An autocomplete list will appear and be updated in real-time, revealing to me notes in my PKM with those words in their titles.

- Pick a few of them that seem relevant, establishing a link from this MOC note to those notes. This makes referring to those linked notes as simple as command+click from now on.

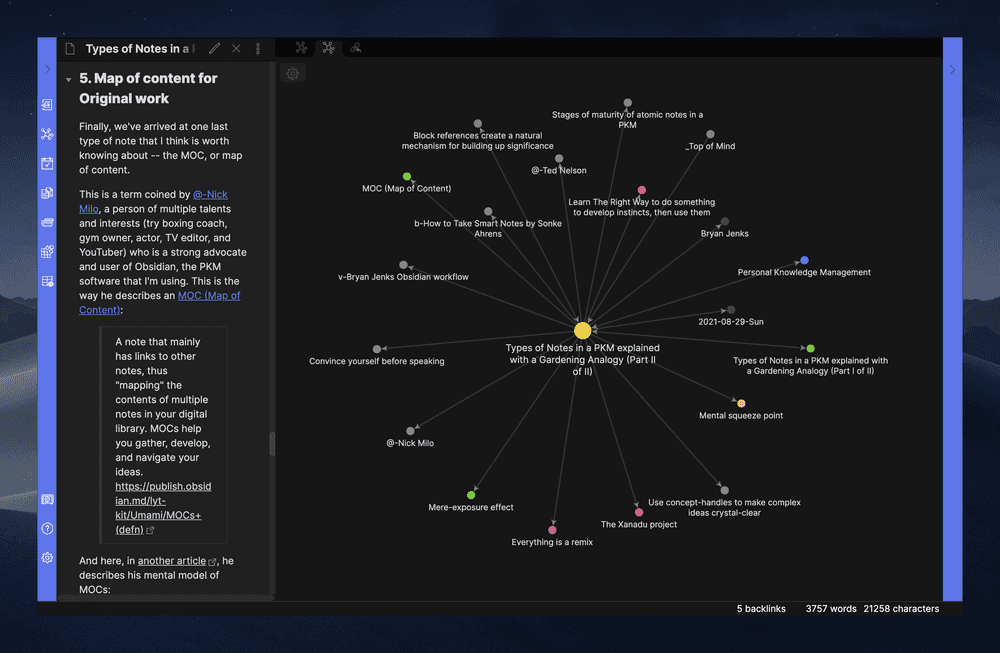

- Open the local Graph View of the MOC note to see the established connections and I increase the “depth” of connections I want to see from 1 to 2.

- Now I’m seeing the notes that the connected notes connect to, and I’m suddenly considering ideas that share proximity to the few ideas I’ve explicitly linked to my MOC. This process feels like I’m pacing through my brain, following each synapse that connects a neuron to another.

- Click-open notes that sound interesting (this is why note titles are important) read their contents, and if they seem relevant, I make more explicit links within the MOC to those notes, accompanying the link with a comment on why I find it relevant. For irrelevant notes, I just close and move on.

By the end of this process, I have effectively ransacked my PKM for relevant notes and laid them all over a digital workbench accompanied by fresh annotations to each note describing how I think they might relate to the topic. And now I’m ready to begin grouping my notes, revisiting each in detail, establishing new connections, and creating an outline for an original (remix?) article.

Here’s what the MOC for this article looked like when it was close to completion, visualised in the Graph View:

For me, this use case alone makes knowing when and how to use a MOC worth it.

Next, let’s talk about point 2: experiencing a mental squeeze point (bottom-up).

In the words of its inventor Nick Milo:

A Mental Squeeze Point is when your unsorted knowledge becomes so messy it overwhelms and discourages you. Either you are equipped with frameworks to overcome the squeeze point, or you are discouraged and possibly abandon your project. This is usually followed by yet another search for the next app that will make all the difference.

The key difference between this bottom-up and the earlier top-down approach is that it is about organising existing atomic notes without a topic in mind. When we experience a mental squeeze point, it helps to go into cataloguing mode.

Purportedly, anyway. Here is where I make an admission: I have not felt compelled to create a bottom-up MOC yet. It may be that I’ll never find a need for it because I have so far been happy with the number of topics that have already emerged from topical, top-down searches. It may also be that I just haven’t crossed a threshold of notes that feels chaotic and in need of mapping. If you want to dig deeper, Nick Milo has shortlisted the why’s of using MOCs that I occasionally revisit to dig deeper into this remarkably versatile note type.

Parting thoughts

Remember that P in PKM stands for personal, so make use of this post to inform, not determine, the things you will do in your PKM. You should have seen that this process also remains malleable for me even though I may already have a working system.

Finally, as you go about implementing some of these ideas in your PKM, try not to do everything at once. You might not even recognise yourself after that. A piece of nonfiction writing advice from Scott Alexander is relevant here: learn The Right Way to do something first to develop instincts, then use them.

Try something for a while and build up a feel for whether it clicks. Discard those that don’t; keep those that do. Then use your instincts after that!